Nostalgia for Finitude

Constructive criticism VERY INVITED leave a comment, send a Bluesky DM, or fire me an email at [email protected]. I'm hoping to wrestle this into some kind of journal submission sometime in the spring.

Once I start shopping this to journals I will probably put this behind the membership wall, so feel free to sign up!

2025 has been a big year for "Artificial Intelligence." As much as many of us hate it, it seems inescapable. Every major software provider seems eager to tout its new AI features. ChatGPT is now the fourth most visited website in the world, gathering more web traffic than any other site save Google, YouTube, and Facebook (a remarkable achievement for a site that has only existed for the last three years). Wikipedia editors, educators, and photographers have all had to wrestle with the implications of AI generated content for their professions.

At the same time, albeit at a much smaller scale, another much older technology is also on the rise. Exact numbers are hard to find, but most signs point to analog film photography becoming more popular than its been in decades. Popular photo news blog Petapixel called last year "Film's Best Year in Decades" and this year looks to continue the trend. Kodak followed investments in film production last year with a return to direct distribution of film to retailers (cutting out Alaris, which bought out Kodak distribution rights after Kodak went bankrupt at the turn of the century). British film producer Harman Technology, famous for its Ilford and Kentmere lines of black and white film, also recently invested in more production and, even more dramatically, released an entirely new color film stock.

I myself also recently started shooting film. Or rather, returned to shooting it after 25 years away. It was something I had resisted doing for a long time, it seemed like a kind of hipster affectation. But when I took my old Pentax K-1000 out of storage and put a roll of film through it "just to see what would happen," I was hooked. Something about the images I got, and the experience of capturing those images was instantly attractive.

In this post, I want to dive into my own experience of shooting film and put that experience into dialog with some scholars of art and culture. Namely Walter Benjamin, who engages with photography both in his famous "Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" and his somewhat less ubiquitous, but still influential "Little History of Photography."

For Benjamin photography was an example of how "mechanical reproduction" of art has outstripped the pace of human labor "Since the eye perceives more swiftly than the hand can draw, the process of pictorial reproduction was accelerated so enormously that it could keep pace with speech," Benjamin explains, going on to state that the speed of film leads inevitably to "sound film" and thus to Paul Valery's prediction that "Just as water, gas, and electricity are brought into our houses from far off to satisfy our needs in response to a minimal effort, so we shall be supplied with visual or auditory images, which will appear and disappear at a simple movement of the hand, hardly more than a sign."

And yet today, ironically enough film photography is now a sort of slow, artisanal, thing. What were once flaws in how it reproduced images: the limitations of its dynamic range and the noise introduced by its grain have become treasured enough that film stocks that emphasize these once bugs (now features) are prized. There even exist widely available tools to mimic these features in digital images.

Understanding the appeal of film in its new, slow, old-technology guise requires the work of William Morris, who celebrated the artist as craftsperson. "You can't have art," Morris once argued, "without resistance in the material." A claim I first encountered in a piece about the Digital Humanities by Bethany Nowviskie. This resistance, this slowness, was essential to the production of meaning in the production of art for Morris. Benjamin, in contrast, was interested in the production of meaning in the interpretation of art. Putting these two very different, but both socialist, theorists into dialog with the current encounter between digital and film photography might tell us something about what the current cache of the analog medium of film tells us about meaning making in our contemporary digital media moment.

In a significant way, I think this encounter shows the limits of how we have imagined building alternatives to the current moment. It shows the insufficiency both of looking backwards towards a less-automated time and of looking forwards towards a future where capitalism collapses under its own weight. It shows us the need for big new visions.

One reason why I think we must turn to Morris to understand the appeal of film is that the visual appeal of film can't completely explain why people are drawn to it. By default, film images do look quite different than digital images, it's true. But simulating this look is easy. The photo editing software I use for images I take with my digital camera, Capture One, has a dedicated slider you can use to add simulated film grain to your images, with a choice of several grain types (harsh, fine, tabular, even "silver rich" whatever that is) in a handy drop down menu. Just this morning I got a marketing email with the subject line promising "The most authentic film emulations in digital photography" from the company I had previously purchased AI denoising software, of all things, from. The email goes on to promise to "bring back the timeless magic of film." Nikon is rumored to be integrating "film grain" simulation into the firmware of its Zf digital camera (which is, itself, a digital camera designed to look like one of Nikon's much older F series film cameras).

All this film emulation shows films cultural cache, but doesn't quite explain why anyone bothers actually shooting the stuff. Instead, this might be about the sorts of "resistance in the material" that Morris claimed were necessary for "art."

Analog film offers many forms of resistance, starting with the need to load a fresh frame of film after taking a picture by pulling the film wind lever, which is directly mechanically linked to the actual film in the body of the camera (on the Pentax K-1000 I usually shoot, at least). When you hit the end of a roll of film, you literally feel resistance in the material as the film pulls taught against its reel. Once, shooting my Nikon F, which doesn't have a working frame counter, I mis-judged how many frames were left and, not yet familiar with the feel of the film resisting being pulled forward, pulled the lever hard enough to tear the teeth of the gear that advances the film through the film itself. The film failed to advance. When I pressed the shutter again, not realizing my mistake, I double exposed the film.

The pull of the film advance is not the only resistance offered by film, there is also economic resistance in this material. Every time I press the shutter button on my film camera I effectively spend at least 30 cents, at current film prices. Not much but for some people, to paraphrase Father Guido Sarducci, that can really add up.

The effort of pulling the film advance lever calls one's attention back to the moment of taking the image. The fact that you are going to spend a few cents on each exposure only heightens this attention. All this conspires to slow down the film shooter, especially compared to someone shooting a current digital camera, which can capture many frames per second if you simply hold down the shutter button and hope to catch something interesting.

This great capture speed is accomplished by virtue of the fact that modern digital sensors are fast enough to be read electronically, without need for a mechanical shutter, robbing the user of a mirrorless digital camera of an actual shutter sound. When I shoot my digital Nikon Z6iii, the shutter sound is simulated. One of my great pleasures when shooting film on my 40 year old Pentax K-1000 is crisp click-slap-thunk of the mirror and shutter moving.

This expense of a roll of film gets even higher if I send my film out to be developed. For color film, I have to do this, but for black and white I've started developing in house. This offers a sort of ideal DIY trifecta: I actually get a better result, at a lower price, faster by doing it at home. I have often sought after but rarely achieved.

The slow pace of hand-developing film creates a kind of ritual, one I find akin to the pleasant ritual of home-cooking. You mix the chemicals. You smell the funk of the developer and the tang of the fixer. You pour each chemical into the tank. You shake the tank gently in a slow periodic rhythm as you wait for the allotted time, not having to quite focus intently but not quite being able to allow your attention to drift off either. After 20 minutes or so, you can take the finished negatives out, and see if you created something beautiful, or just had a... let's say "experience of learning by making a mistake."

So the slowness of film, enabled in part by its expense, becomes a reason for shooting it. The idea that slowness in art is a positive good, one that gives the artist pleasure and encourages their craft is very much an argument supported by Morris. "The minute you make the executive part of the work too easy, the less thought there is in the result," he argues just before giving his famous quote from above. He continues, "The very slowness with which the pen or the brush moves over the paper, or the graver goes through the wood, has its value." The attention paid even to the quasi-mechanical work of developing film, standing over the bathroom sink slowly shaking the Paterson Tank for half an hour, has value.

The idea that film photography could become the object of a slow ritual would probably be at least somewhat upsetting to Benjamin, for whom the destruction of slowness and ritual was the whole point. It is the speed at which photography both captures and reproduces images, its productivity that gives it revolutionary potential. Benjamin proclaims that photography is "the first truly revolutionary means of reproduction" precisely because "mechanical reproduction emancipates the work of art from its parasitical dependence on ritual."

The destruction of ritual is, for Benjamin, commensurate with the destruction of what he calls the "aura" of a work of art, it's "authenticity" or as he puts it "the essence of all that is transmissible from its beginning, ranging from its substantive duration to its testimony to the history which it has experienced."

This destruction of "authenticity" may seem to be a destructive, negative function of mechanical reproduction. Confused undergraduates often read it as such. In their defense Peter Osborne and Matthew Charles suggest Benjamin himself was conflicted about the notion of "aura." "On the one hand," they write, "with regard to some of his writings, Benjamin’s concept of aura has been accused of fostering a nostalgic, purely negative sense of modernity as loss—loss of unity both with nature and in community (A. Benjamin 1989). On the other hand, in the work on film, Benjamin appears to adopt an affirmative technological modernism, which celebrates the consequences of the decline." They inform us that no less a figure than Theodore Adorno was disappointed in Benjamin for his turn to celebrating the destruction of the aura writing that he was "disturbed" at how Benjamin had "rather casually transferred the concept of the magical aura to the ‘autonomous work of work’ and flatly assigned a counter-revolutionary function to the latter."

Indeed in "Mechanical Reproduction" Benjamin makes this argument quite sharply pivoting from the destruction of "aura" to a section devoted to developing how the ability to mechanically reproduce art strips away its "cult" function, a function Benjamin believes extends to the notion of "art for art's sake." The cult, ritual function of the work of art Benjamin believes depends on the existence of privileged, authentic "originals." Since no single photograph can really be deemed "authentic," as "From a photographic negative [...] one can make any number of prints," photography leads to a situation where "the total function of art is reversed. Instead of being based on ritual, it begins to be based on another practice—politics."

In this, Benjamin seems to be following closely the logic Marx gives in the Communist Manifesto, where he famously argues that as the bourgeoisie tears the "sentimental veil" away from various aspects of life, from the family to religion to nation, "All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind." When the conditions of exploitation humans are embedded in under capitalism is faced with these sober senses, Marx believes the only path is towards authentic class consciousness. So too, Benjamin seems to argue that the decline of aura and cult in art leads towards authentic mass politics.

Benjamin, then, would almost certainly be dismayed at the return of film to the realm of ritual. It's not only the slowness of film, compared to digital reproduction, that gives it a ritual quality. The visual flaws of film have become a source of authenticity, of "aura" in the digital age. Film grain, the distinct stippled appearance left behind in a film image by the underlying bits of the photosensitive chemicals that formed it, has become particularly prized. Ironically, this means that a kind of reversal of prestige has occurred in film much as it has in food. Just like how "rustic" uneven bread has become high prestige in a world where fine-textured bread is easily mass-produced, types of film that were once considered low prestige, because of their graininess, are now prized and formerly "professional grade" films that were valued for their "clean" low-grain appearance are passed over.

The unique qualities of film "stocks" (the different formulations of film produced by different manufacturers) have been imbued with aura, by both users and manufacturers alike. Motion picture film stocks, which can be "respooled" and used in 35mm still cameras, are particularly prone to this, given the shared cultural value of movies. Users of Kodak 5222 will often tell you that this was the stock that Raging Bull, Schindler's List, and Memento were shot on. Lomography, a film and camera company spun out of a Viennese art movement inspired by the LOMO (Leningrad Optics and Mechanics Organization) camera - as the name implies, a Soviet copy of a Japanese compact camera - markets their "Berlin Kino" film thusly: "Inspired by the New German Cinema sweeping through Europe in the 1960s, our Kino Films are extracted from rolls of cine film produced by a legendary German company that has been changing the face of cinema since the early 1900s."

Most internet sources believe Berlin Kino to be respooled ORWO film, which puts a bit of a dent in the romance of the ad copy since ORWO was based in East Germany and New German Cinema was West German, but details like this are mostly irrelevant to the narrative power of aura.

So what's happening here? Is film reactionary, drawn into the romance of the past and away from the arc of progress? Are the kids dabbling with film inadvertently dabbling with fascism? Is Morris, celebrating the value of ritual and slowness, also being taken in by aura and holding back the True Consciousness that will bring Revolution? He was, after all, one of the very first NIMBYs.

I don't think so, not quite. It's past focused, and that's a problem as we'll see. But not necessarily reactionary. Instead, I think the resurgence of film in the era of the hyper-digital (of AI) shows why the kind of melting of all that is solid into air that Benjamin seems to long for was never quite as emancipatory as he had hoped. It shows why the Orthodox Marxist approach to "culture" as something to be cleared away never quite pans out. It points to another way forward, if we think about alienation and creative work differently.

Morris approaches the ritual nature of art not as a consumer of a finished piece overawed by ceremonial presentation, but as a craftsperson embedded the pleasant habits of production. For Morris, direct contact with the hands-on activity of craft is an essential part of the pleasure of creativity. "Anything that gets between a man’s [sic] hand and his work," he writes, "is more or less bad for him. There’s a pleasant feel in the paper under one’s hand and the pen between one’s fingers that has its own part in the work done."

In her piece, "Resistance in the Materials," Bethany Nowviskie examines Morris's attitudes towards craft rituals, and asks if they are things that can be extended towards the digital. Nowviskie points out that Morris (who of course had no experience with the digital, having died decades before the first digital computers were built) held even the typewriter in contempt, calling it "out of place in imaginative work," and insisted on writing with a quill pen. She points out what seems to be a contradiction in Morris's thought when dealing with the typewriter. After a long passage praising various forms of resistance in the materials, Morris criticizes the typewriter by quipping "with a machine, one’s mind would be apt to be taken off the work at whiles by the machine sticking or what not."

For Nowviskie, this is somewhat inconsistent. Why is this form of resistance, "the machine sticking or whatnot" bad and the others good? She asks if this isn't "just another kind of maker’s resistance? A complication we might identify, make accessible—which is sometimes to say tractable—and overcome? After all, the “executive part of the work,” its carrying-out, should never be made “too easy.” Isn’t a sticky typewriter—as something to be worked against or through—a defamiliarizing and salutary reminder of the material nature of every generative or transformative textual process?"

Nowviskie goes on to reconcile this apparent contradiction. She explains that Morris is displeased with resistance that makes him feel passive:

When Morris frets about “the machine sticking or what not,” it is with an uncharacteristic voice. He offers the plaint of a passive tool user—not of the capable artisan we are accustomed to, who might be expected to fashion and refine and forge an intimate relationship with the instruments of his work. The resistance in the typewriter Morris imagines, and the resistance digital humanities novices feel when they pick up fresh tool sets or enter new environments, is different from the productive “resistance in the material” encountered by earlier generations of computing humanists. It’s different from that happy resistance still felt by hands-on creators of humanities software and encoding systems.

The example of photography might help explain why the negative resistance felt by the "passive tool user" might be, at least in some cases, keenly felt by users of digital tools - and not only the novice or inexperienced users that Nowviskie imagines above. Ironically, one reason digital tools might make users feel "passive" is because these tools give us too much choice.

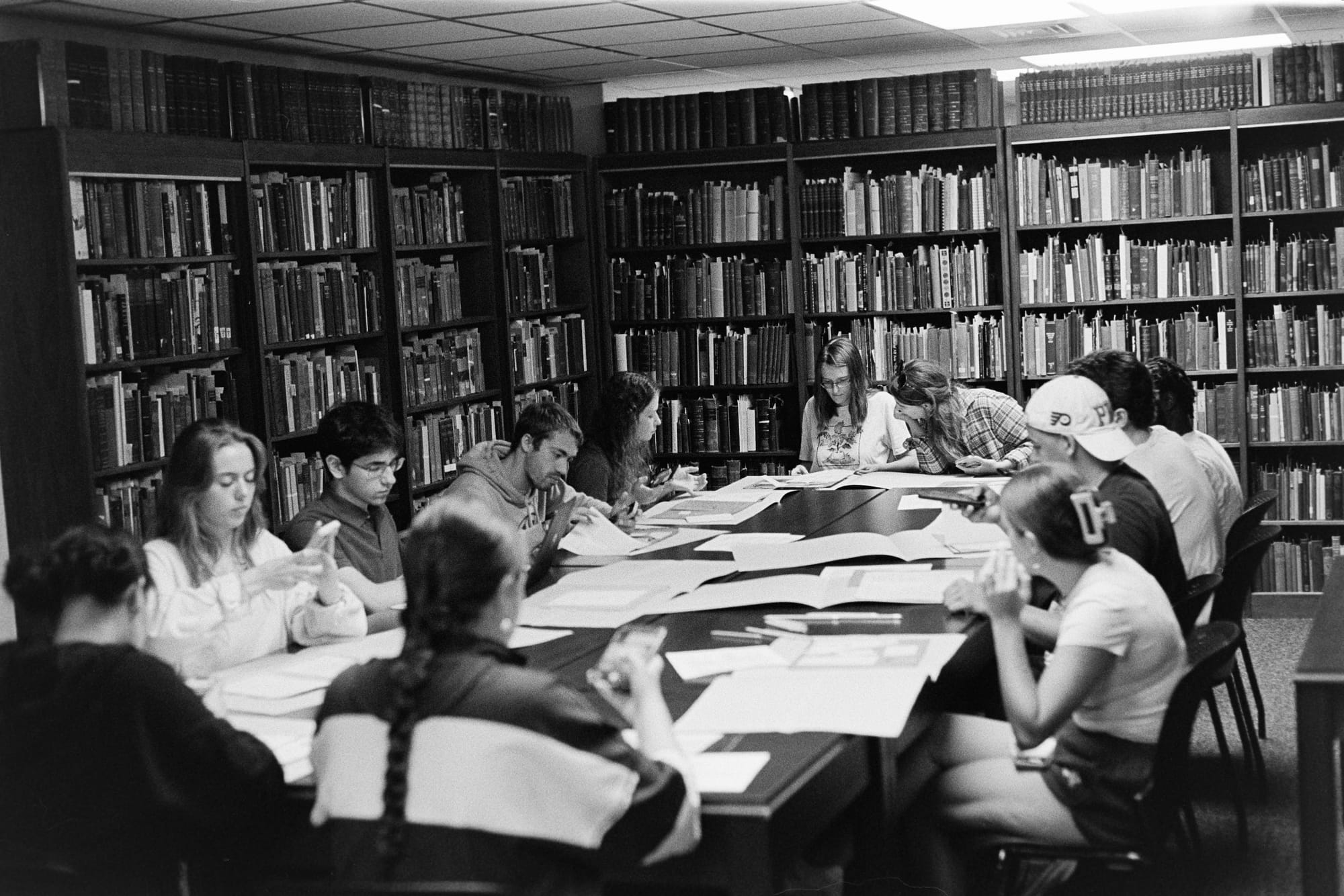

To illustrate this, let's return to the visual aspects of film photography. Here is one of my very favorite film images I've captured so far:

Just look at the light on the water. Look at the highlights in the lower right, just look at them. And this was captured on film stock of no great renown, just humble Fuji 400 from the CVS. No aura there, the kids on the internet say it might be just rebranded Kodak Ultramax 400 (the least cool Kodak Film).

I know what I said, this can be replicated with a digital image, and of course it can. There is nothing magic about film (no matter what an ad selling a simulation of film tells you). It captures light through chemistry. A digital sensor captures light through quantum physics and it captures more information out of that light. More resolution, more dynamic range. If you want the digital image to look like the film image, all you have to do is selectively throw some of that away.

But selectively throwing away data from your digital image is a choice. One of an almost infinite array of choices that confronts the user of a modern digital camera (or indeed anyone living in our modern digital world).

An example comparing analog to digital capture might further demonstrate how these two media deal with choices differently. When I slot a roll of film into my K-1000, I set a little dial on the top that indicates the "speed" of the film, which is a measure of how sensitive it is to light, with higher "speeds" being more sensitive. The Kodak Gold I often shoot for color is rated at speed of 200 ISO (for the International Standards Organization, which set a unified scale for film speeds in 1974 replacing the prior ASA - American Standards Association - scale, which my K-1000 speed dial is still labelled in), whereas the Ilford HP5+ I usually shoot for black and white is rated at 400 ISO. More sensitive film allows you to shoot with a smaller aperture lens (creating sharper images) or with faster shutter speeds (freezing motion). Once I load the film in my K-1000, that choice is set for the next 36 frames, with no way to alter it.

In contrast, a digital sensor has no set "speed." It can use signal amplification to alter its "speed" on the fly. The consequence of this amplification is increased noise, which used to serve as a limit to this but lately doesn't so much anymore. My Z6iii, which has a very good sensor but not the very best available, will happily shoot very low noise images at speeds of 1600-3200 ISO and will capture a usable, if noisy, image at speeds up to 12800 ISO.

The result of this is that many photographers (myself included) shooting current digital cameras will utilize a method called "manual settings auto iso" when shooting. This means the photographer chooses both the shutter speed and aperture to shoot at and allows the camera to automatically adjust the ISO of the sensor to create a correctly exposed (not too bright or too dark) image given those inputs. In extreme circumstances, one can overwhelm the sensor and over or under expose your image (most often when moving into bright sunlight with settings for a much darker scene, resulting in over exposure because the camera can't adjust the ISO any lower) but mostly this works. In theory this gives the photographer almost total creative control, letting them set shutter speeds and apertures as they please to achieve various effects (like motion blur at slow shutter speeds or crisp frozen action at high shutter speeds, or high sharpness at small apertures or throwing the background out of focus and isolating the subject at large apertures) without worrying about exposure.

What I noticed when I started shooting film, however, was something counter intuitive. I was often getting better, crisper frozen action in the portraits I was taking with my (relatively) slow ISO 400 film than I was getting with my digital camera, which, again, will shoot ISO 3200 without breaking a sweat. That meant the digital ought to have allowed me to set a higher shutter speed and capture the action better. But I didn't? At first I was confused.

But then I understood. When shooting portraits, I was cranking my aperture wide open to blur the background, since the ISO of my film was fixed I had to crank the shutter speed faster to compensate. On digital, the camera just compensated for the larger aperture by setting a lower ISO, and I never paid attention to my shutter speed. So, resistance in the materials limiting my choices lead me to pay more attention and make better images.

Except that, having learned this lesson from film, I have now applied it to my digital photography. I find myself watching my shutter speed much more carefully and thoughtfully. So this points to a pedagogical value to resistance in the materials, and probably that's an important thing to consider now, with the rise of ed-tech and its promises to make learning "frictionless." But its not quite the artistic value Morris promised.

To fully get at that, consider digital post-production, where a photographer is faced with even more choices. Should I tweak the contrast, the saturation, the exposure curve? Should I crop just one piece out of the dazzlingly high resolution image (which has, after all, too many pixels for any normal display to even render)? Should I apply one of the many custom LUTs (basically fancy instagram filters) available for download or purchase to my image? Should I attempt a naturalistic presentation? A stylized one?

It's not that I can't make those choices. I can, with at least some pleasing results:

But still, navigating them all feels somewhat random. I always find myself wondering "is this choice having the effect I intended? Is it doing anything? Should I be doing this some other way?"

I would suggest this is a common experience for many users of digital tools. Faced with a near infinite array of settings, how do we know which is meaningful? One feels overwhelmed, passive, unable to move forward. Faced with an infinity of choice, with a lack of resistance from the tool itself, it is we who seize up, who "stick."

In contrast, with film the resistance in the materials limits our choices and leads to a process that feels more under control. I choose some ingredients (a film stock, a developer), a technique (maybe I develop the film at "box speed" or maybe I "push process" it, intentionally over-developing under-exposed film for more contrast and grain), and then I follow the recipe (perhaps with some tweaks and adjustments based on the last time I made it) and get my results. Our feelings of being in control of the process, of understanding the resistance in the materials that confronts us, limits our feelings of alienation. That connection to the work that Morris finds pleasurable, those who shoot and develop film find pleasurable as well.

But this pleasure comes at a price. Literally. Each frame costs 30 cents. My productivity of images using film is significantly lower than on digital, where I can capture 20 frames per second with no monetary input for each frame.

These limitations haunted Morris as well. A 2023 profile of him in Jacobin is surprisingly flattering, given that publication's recent lust for the blood of the "Professional Managerial Class," but notes that his home goods company, which he founded in the interest of "producing exquisite books, chairs, and tapestries for their own sake, for their use value," ultimately "catered almost exclusively to the upper-middle-class marketplace, despite his democratic hopes for its products." Somewhat wryly, Jacobin author Matthew Beaumont notes "Morris thus lived the dialectic described by Walter Benjamin in his famous claim that “there is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.”

It is the breaching of these limitations by the productive power of capitalism that gives Benjamin, like other early 20th century Marxists, hope. Except for Benjamin it is the cultural limits of the "superstructure" rather than the material limits of the "base" which he hopes will melt into the air.

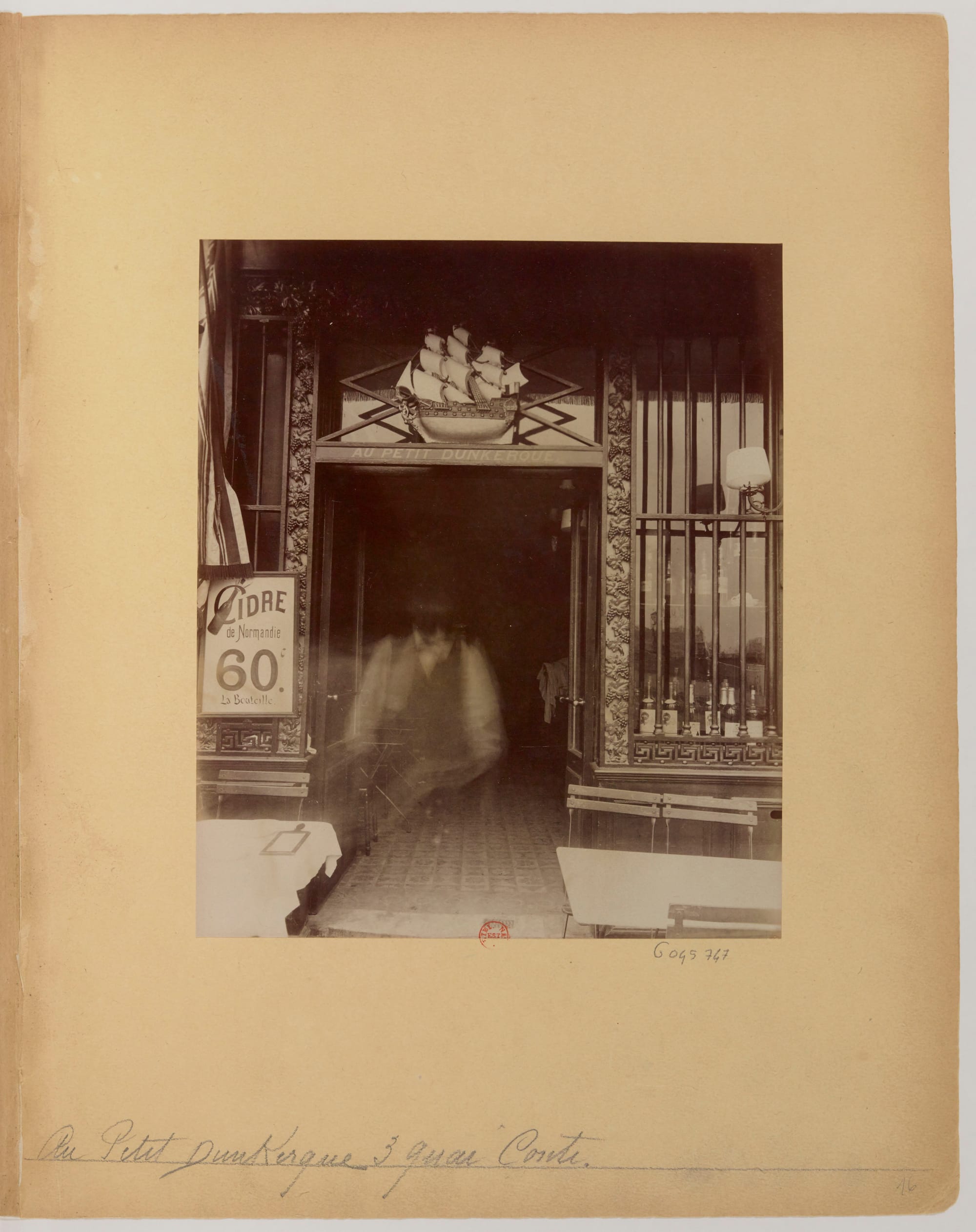

In his 1931 "Little History of Photography," Benjamin includes the same language celebrating the destruction of the "aura" by photographic reproduction he would include in "Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" that I have quoted above. In this version, he pivots from the destruction of the uniqueness of the work of art to a discussion of the photographer Eugene Atget, whose late 19th and early 20th century photographs of Paris document such common, ordinary items as "a long row of boot lasts; or the Paris courtyards, where from night to morning the handcarts stand in serried ranks; or the tables after people have finished eating and left, the dishes not yet cleared away - as they exist by the the hundreds of thousands at the same hour."

Benjamin argues that this attention to everyday objects, enabled by the remarkable productivity of photography, both in Atget and in the Surrealist photographers who he sees Atget as prefiguring, strips back the aura of aesthetics and "gives free play to the politically educated eye, under whose gaze all intimacies are sacrificed to the illumination of detail." Everyday objects, the "boot lasts" and "courtyards" and "dishes not yet cleared away" in Atget can be seen with sober senses, and their conditions truly understood.

At the same time that he argues that photographic productivity might elevate the everyday subjects of Atget, Benjamin holds that photographic duplication will reduce the former cult status of the singular work of Art. He believes that as Art is demystified by access, by the mechanical reproduction that makes formerly cult objects into objects of exchange, class awareness can step to the fore. In "Little History of Photography" he writes:

Everyone will have noticed how much easier it is to get hold of a painting, more particularly a sculpture, and especially architecture, in a photograph than in reality. It is all too tempting to blame this squarely on the decline of artistic appreciation, on a failure of contemporary sensibility. But one is brought up short by the way that the understanding of great works was transformed at about the same time the techniques of reproduction were being developed. Such works can no longer be regarded as the products of individuals, they have become a collective creation, a corpus so vast it can be assimilated only through miniaturization. In the final analysis, mechanical reproduction is a technique of diminution that helps people to achieve control over works of art - a control without whose aid they could no longer be used.

And yet even as he celebrates the kind of broadly distributed control over art that photography brings consumers Benjamin casts serious doubt over the effects of broadly distributed photographic production. In the very same paragraph as the passage above, Benjamin quips that "the amateur that returns home with great piles of artistic shots is in fact no more appealing a figure than the hunter who comes back with quantities of game that is useless to anyone but the merchant. And the day does seem to be at hand when there will be more illustrated magazines than game merchants." The figure of the merchant in Benjamin's analogy brings to the fore the Marxist divide between use and market value. Rather than "democratize" the use value of artistic production, Benjamin here reads photography as collapsing its market value through over-production. A classic Marxist take on the self-collapsing productivity of capitalism, applied to visual representation.

In the 21st century, the glut of images that Benjamin observes amateur film photographers capturing has grown to a veritable tsunami of visual content. Smartphone cameras have become remarkably capable devices, with technical image quality in many ways akin to the best dedicated digital cameras a recently as a decade ago. Almost everyone has them in their pockets almost all the time. We have become accustomed to news events being recorded from multiple angles by multiple vernacular photographers. Almost any photograph of a recent political protest captures within it multiple other photographers recording the same image. In 2012, a mere five years after the introduction of the iPhone, The Onion released a satirical news video "Police Slog Through 40,000 Insipid Party Pics to Find Cause of Dorm Fire," which imagined the sparking of an NYU residence hall fire being caught in hyper-detail by party goers taking snapshots.

Satire was already trailing reality, finding comedic bite only by imagining the quotidian as newsworthy. Occupy Wall Street and Tahrir Square had already been livestreamed. I remember the video of the night Zuccotti Park fell, grainy front-facing iPhone camera footage in the dark, straining to pull image from noise. The line of police over the shoulder of the young caster, batons and riot shields shining dully in the streetlight.

What is someone interested in Photography as a visual medium, as a means of expression, to do in the midst of such a glut? How can they produce images that anyone will want to look at, when we are all bombarded by a visual feast 24 hours a day? It is possible to build dedicated digital cameras that can beat smartphone cameras technically, but to do this you need to build very large very sophisticated digital sensors and mate them to very large very sophisticated lenses. This means these devices are quite expensive indeed. My Nikon Z6iii is considered a "mid-range enthusiast oriented" full-frame mirrorless digital camera, not the top of the line. It cost almost $3000 with its basic kit lens. Real pros shoot its big brothers the Z8 or Z9, which cost a couple thousand more, and use pro-grade lenses like the 50mm f1.2, which is another $2500 (we'll leave aside, for now, the issue of even more eye-wateringly expensive photographic equipment, like medium format gear and dedicated cinema rigs). When I mention even my Z6iii in a photography Discord I sometimes frequent I can almost hear some of the other users there, who tend to be 20 something artist types, roll their eyes at my hopelessly bougie expensive camera.

No, what they shoot, mostly, is film. Because film will capture an image that looks distinct from any camera phone and you can get a perfectly good used film camera (and they are almost all used these days, all of these kids are shooting cameras older than they are) for $150. Granted, you can spend an awful lot on the film, but that's broken down into bite sized $8-$12 spends that are more manageable for the young artist. Many of the Discord chat users I talk to are VERY dedicated to the least expensive film stocks: the Harman company's budget Kentmere line or even Czech Fomapan, which are notoriously flawed films but if your goal is to create something unique you can lean into those flaws!

Film then, is an approachable way to stand out in the world that over produces (in the Marxist sense of the "crisis of overproduction" more than in the Hollywood sense of an "overproduced" look, though the second also applies) digital images. What's more, it's an approachable way to transform the visual world in a way that feels artistically satisfying. Ur-Street-Photographer (a genre closely related to Benjamin's flaneur) Garry Winogrand once famously said “I photograph to find out what something will look like photographed.” In the current moment, though, there is no mystery about what something in our lives will look like when captured by a smartphone sensor. We've all seen that image before, and what's more the smartphone is carefully calibrated to produce an image that conforms to a particular model of "realism" (which, in turn, our own sense of the realistic has evolved towards as smartphone photography has become part of our quotidian prosthetic memory). The film camera restores the pleasant mystery of photography. When I press the shutter on my K-1000, I find myself wondering what I will see when I eventually develop the film (and sometimes catch myself looking at the back of the camera for a preview image that will never appear).

On the one hand, the struggle to have a photograph seen in a world awash in photography points, as Benjamin suggests, to the exchange value of art. On the other hand, Winogrand's aphoristic assertion that he takes images "to find out what something will look like photographed" points to the use value of art. In particular, it points to the use value of art for the artist, the way in which the process of creating is a surprising, meaningful and pleasurable experience for those who create images as well as those who consume them. In this, Winogrand almost recalls Morris's musing on the "pleasant feel in the paper under one’s hand and the pen between one’s fingers."

For Morris, anything that takes away that pleasant sensory connection between artist and the embodied work of creating art is "bad for" the artist. Nowviskie is right to point out that Morris is, like all of us are, perhaps too connected to his own familiar forms of embodied practice to understand how newer practices remain embodied - just in ways he doesn't recognize, but nonetheless Morris may be observing something real. More productive, efficient, mechanical means of (re)producing works of art may indeed rob the creator of direct sensory feedback from the creative process, whether that is the typewriter taking away Morris's ability to feel the paper beneath his pen, or my mirrorless camera taking away the click-slap-thunk of my SLR's shutter or the tug of the film beneath its advance lever. This represents a kind of alienation for artists, not so much economic as phenomenological: an alienation from the embodied process of making.

This kind of alienation is, in realms outside the cultural, justified by the very real need for more efficient production of goods and services. As a gardener, I can tell you that you do in fact lose a meaningful experiential connection with your food when you don't raise it yourself. As a student of history, I can tell you that our ancestors who fully had that connection paid for it by periodically watching their children starve to death. Industrial large-scale food production is deeply alienating and very problematic in many ways. It also saves lives.

Cultural production is different. We have never needed more cultural productivity. There has never been a famine of song, a depression for poetry, a drought of visual culture. We have probably always had too much of the stuff. The kinds of cult and ritual functions Benjamin ascribes to pre-modern art may well have served to sort and limit the amount of cultural production even then by ascribing only some works ritual significant. No need to go see every last one of your clan-mates wood carvings, only the cult ones thanks. At the very least, the written word produced so much culture as to generate complaints. The book of Ecclesiastes includes a gripe about how “of making many books there is no end.” By the dawn of print, Ann Blair tells us:

Complaints about an overabundance of books became a well-worn refrain throughout early modern Europe and were used to justify any number of postures: railing about the base commercial motives of printers who produced whatever sold without a care for quality or intellectual merit, mocking the vanity of bookish learning, worrying about the end of civilization from too many people writing (bad) books and no one reading good ones anymore, or on the contrary worrying that authors with new ideas would be discouraged from writing by the mass of what already existed.

Given this constant over-abundance of culture, technologies that increase the productivity of cultural outputs are solving the exact wrong problem. We do not need more of the stuff!

Instead, the economic problem of culture is how to fairly distribute the material productivity of modernity to those engaged in creativity. Here, since the dawn of copyright, exchange value has entered the picture, allowing some creatives to sell work for currency. This was always an imperfect system, necessitating the production of artificial scarcity to keep exchange values high enough for creatives to make a living. This meant marginalizing a variety of potential cultural producers. In 1906, John Phillips Sousa decried the displacement of vernacular amateur musical practices in his "Menace of Mechanical Music." He predicts record players will displace amateur and semi-professional musicians in a variety of settings, from parents singing to children, to "small country bands." At the close of his essay he predicts that even in rural hunting camps where once "around the camp fire at night the stories were told and the songs were sung with a charm all their own" recorded music will displace the amateur as "the ingenious purveyor of canned music is urging the sportsman, on his way to the silent places with gun and rod, tent and canoe, to take with him some disks, cranks, and cogs to sing to him as he sits by the firelight."

In more recent, scholarly take on the same issue, Andrew Ross Sorkin points out in his "Technology and Below-the-Line Labor in the Copyfight over Intellectual Property" that copyright in musical recordings only provided income for some creative professionals. He argues that those who analyze the dawn of copyright in music with the first licenses of compositions for player pianos "have nothing to say about the human piano players whose livelihoods were radically affected both by the mechanization of piano playing and by the congressional ruling. The only "musicians" who figure are the composers whose full authorial rights were being compromised by the industrial piracy of the day."

Artificial intelligence, the ultimate "productivity" tool for churning out both images and text with minimal effort, only exacerbates this problem. Now images and text can be "generated" with almost no human effort at all! This is already showing an impact on the job market for freelance writers and photographers.

If anything could be expected to finally collapse the capitalist system of cultural production under its own weight, it would be this. And yet, that does not appear to be the case. Even now, with all that is solid truly melting into air, an automatic transition to class consciousness does not seem to be in progress. Some writers and photographers, those lucky enough to already have "Intellectual Property" are joining lawsuits attempting to enforce those property rights on AI companies. Others, attempting to navigate the evaporation of deeply unsexy but lucrative jobs like taking corporate headshots are being advised to "move upmarket," chasing the sponsorship of the ultra-rich as their market value declines.

Meanwhile, the kids with no established Intellectual Property to protect or corporate headshot gigs to lose are shooting film. Privileging the slow process Morris championed over a finished product that has no value anyway. In a sense, they are engaging in a version of what Matt Seybold has called "Print as a Rent Strike." They are consciously refusing the technology that does not need them to produce, and engaging consciously in a creative process.

Except that this creative process will not pay the bills! Support for it will have to be socially negotiated to be broadly accessible. By the end of his life, Morris knew this, having seen his small hand craft studio fail to reach a broader audience. A simple turning back does not solve the underlying social-economic issue.

So there we have it. The unanswered question: how do we arrive at a society that can support the overabundant creative impulses of its people? While the theorists I engage with here are very old sources, the answers they give to this question remain at the base of many of our current attempts to wrestle with it. Benjamin's Marxist confidence in the inevitable self-collapse of capitalism has echoes in the various left-formulations of "accelerationism." More significantly, it returns to us whenever left movements attempt to "clear away" mere cultural issues to reach the supposed bedrock of class relationships.

This attempt always fails, and film shows why. Even a technology as revolutionary and mechanical as film is still placed in history. It will attain an aura. All that is solid will never actually melt into air. It will sublimate, recrystallize, return in new and strange forms.

Meanwhile, Morris's desire to return to the authentic, the handcrafted, is still incredibly widespread. From film photography to slow food, the desire crops up again and again. Film helps us understand why, it answers real needs for feelings of control over a creative process. It highlights a human desire to engage in creativity that Benjamin's more doctrinaire Marxism tends to miss.

But without economic support, this process cannot be accessed by the masses! So the impasse remains, looking for someone clever to take it up.

Member discussion